What is Parkinson’s Disease?

Parkinson’s Disease is a condition that affects the brain and can impact a person’s ability to move smoothly. Parkinson’s Disease results in the loss of a chemical called dopamine in a specific part of the brain (1). Dopamine is important for controlling body movements, making them smooth and coordinated (1). Without enough dopamine, people with Parkinson’s Disease may experience tremors, muscle stiffness, and difficulty with movement.

Body movements and physical activities are an integral part of our daily life. Therefore, the daily life of people with Parkinson’s Disease is often affected.

Movements and Activities are Part of Our Daily Life

Our daily life involves different body movements and activities. From the moment we wake up in the morning, we engage in physical activities and our body is constantly in motion performing various activities throughout the day. Some of these activities are routine and mundane, like brushing our teeth, eating breakfast, or walking to work. Others are more dynamic and require greater effort and skill, like playing sports or dancing.

But how are these activities controlled? How does the brain coordinate the complex process that allows us to perform such a diverse range of activities with precision?

How are Movements and Activities Controlled?

Our body movements and activities are influenced by two different types of higher brain control: automatic and attentional (2,3).

Automatic control allows us to perform activities without having to consciously think about every detail, such as walking or eating.

Attentional control, on the other hand, involves our voluntary focus on the specific movements we need to make to do an activity, like when we need to make precise movements while playing sports.

The balanced interaction between these two types of control is important for body movements and activities, and dopamine is an important part of keeping this balance.

How is Control Different for Patients with Parkinson’s?

In Parkinson’s Disease, lower levels of dopamine in the brain lead to changes in how we balance automatic and attentional control (4–6). As a result, people with Parkinson’s Disease often experience decreased automatic control of daily motor activities, such as walking. In order to walk normally, they may have to pay more attention to what they’re doing in order for it to happen ordinarily (2,6,7). As a result, people with Parkinson’s Disease might need strategies to enhance their awareness and be mentally engaged in their body movements so that they can do them ordinarily.

Can Patients Re-Learn Movements?

When we want to stay mentally engaged in an activity, there are a few things that can help improve our attention and awareness of the activity we are doing. These include:

- getting feedback (reinforcement)

2. being cued

3. being motivated (4,8)

Feedback helps people know what they are doing well and what they need to improve. For example, a soccer coach might tell an athlete that the way they handled the ball by using the correct part of their foot was excellent.

Being cued, on the other hand, makes people aware of how to improve. For example, in exercise programs, trainers might use specific verbal cues about how you’re positioning your feet when performing squats to help you focus on improving your performance.

Motivation involves receiving a reward for doing the correct movement. In the case of our soccer player, scoring a goal during a well executed breakaway would motivate them to repeat that performance at the next opportunity to do so.

Exercise and rehabilitation interventions for people with Parkinson’s Disease also use these techniques to target mental engagement and to increase attention to body movement (6). When people with Parkinson’s Disease become more mentally engaged with the practice, they can “re-learn” activities that used to be automatic, such as walking or eating.

Biofeedback in Parkinson’s Disease

Biofeedback is a way to help you understand what your body is doing through the use of technology. It is especially important because it helps people see what they are doing well and what they need to improve.

There are different ways to use biofeedback. This includes using feedback that you can see, hear, or feel through vibrations to improve body movements (9–12).

Biofeedback has been used in the rehabilitation of symptoms of Parkinson’s Disease such as difficulty walking, loss of balance, falling, and posture problems (9–13). For example, people with Parkinson’s Disease may use a wearable device that provides vibrations that helps initiate and maintain regular steps during walking. The biofeedback focuses the person’s attentional control on walking and helps them perform the correct movements, which can be difficult to do on their own .

In view of the promising findings of using biofeedback in Parkinson’s Disease, we can’t help but wonder how helpful it would be to implement biofeedback for swallowing therapy as well. Why would this work? Because swallowing is a coordinated muscle activity that many people with Parkinson’s Disease experience problems with.

Biofeedback in Dysphagia

Swallowing exercise often involves complex movements that can be challenging to learn. This is because swallowing is something we do naturally without being taught how to do it. Therefore, it might not be easy to learn how to swallow consciously because it is not something we think about doing.

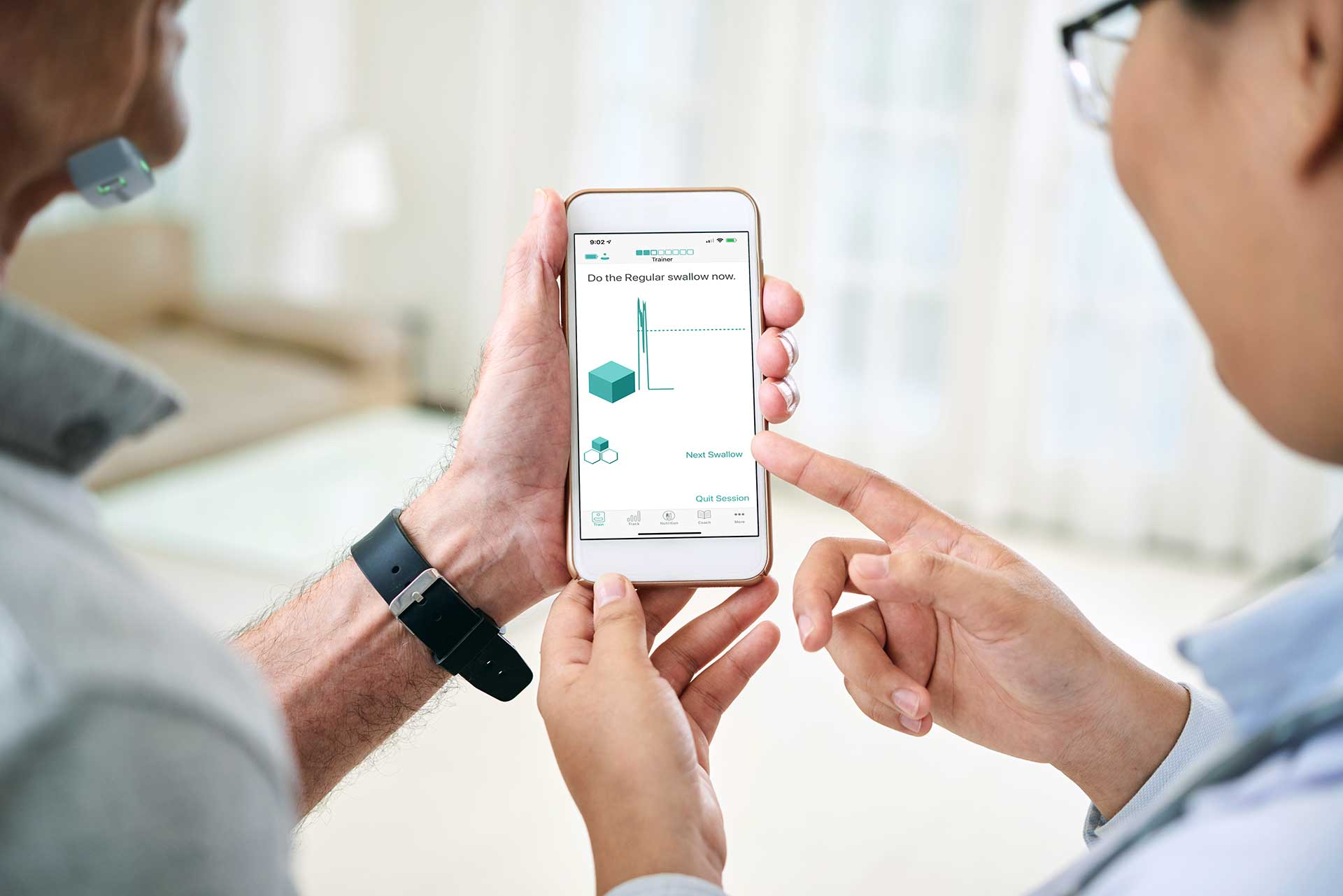

Biofeedback during a swallow means that we can see how our swallowing muscles are working. It has been found that biofeedback helps patients learn swallowing exercises that might be hard to grasp more easily.

In swallowing therapy, one type of visual biofeedback called surface electromyography (sEMG) has been used to teach difficult exercises. It can also be used to monitor patients’ performance during swallowing exercises. By using special sensors that detect the muscle activity (sEMG), patients can see how their muscles contract during swallowing exercises. This helps them compare how they want their muscles to work with how they actually work, so they can improve their swallowing (14–16).

Biofeedback for Dysphagia in Parkinson’s Disease

Biofeedback, like sEMG, has been extensively used alongside swallowing exercises in dysphagia therapy in several patient populations with promising results (14,15,17–20). There are studies that are starting to show the benefit of using biofeedback for dysphagia therapy in Parkinson’s Disease as well (16,21).

Because of the benefits that visual biofeedback brings as a mental engagement element for people with Parkinson’s Disease, the use of biofeedback alongside swallowing exercises in dysphagia therapy for people with Parkinson’s Disease could be promising. Current research is underway at the University of Alberta to study the use of biofeedback alongside swallowing exercises for Parkinson’s Disease.

Biofeedback is Promising for Parkinson’s Patients

In conclusion, Parkinson’s Disease is a condition that affects the brain and can lead to difficulties with movements and daily activities, including swallowing. People with Parkinson’s Disease may require strategies to enhance their attention to their body movements in order to perform them ordinarily. Biofeedback is a promising technique that has been used in rehabilitation of Parkinson’s Disease because it can help enhance their attention to the activity at hand. Using visual biofeedback in dysphagia therapy for people with Parkinson’s Disease may show promise due to the benefits it brings as a mental engagement element.

References: